Lately, there’s been a spate of books featuring deaf and hard-of-hearing characters, across audience and genre. Some of them are written by hearing authors, others by deaf ones, some by people who might consider themselves in between.

Every time I’ve caught wind of one of these books, I’ve gone through a cycle that is now bordering on ritual. 1. I get excited, try to get my hands on a copy of the book. 2. I read the book, and think, wow, I’d like to review this. 3. I pitch a review. 4. Radio silence (ha ha).

Now, there are a few possible reasons for this…

…and like most things, the real answer is probably a combination platter:

Media criticism is dead.

My pitches are not shiny enough.

People are ableist and don’t understand that deaf people are a marginalized socio-linguistic group with our own culture, history, values, and norms. That is, they don’t think we have anything to add to the conversation.

People are ableist and do understand that deaf identity exists, but assume that if the author is hearing, I’ll just want to dump on the book. Once, in inquiring about a potential review and mentioning that I think my perspective as a deaf person could be valuable, I was told I shouldn’t try to review a book disliked, (which, is a whole other ball of wax). But the thing is, I did like the book. While I’ll always seek to champion fellow deaf authors, I also think demanding that authors’ identities match their characters’ is silly, an attempted shortcut at the research, empathy, and, you know, good sentences, required to make a book good.

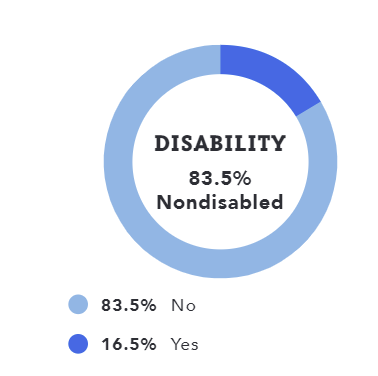

It will come as a shock to no one that disabled people are underrepresented in the literary world, on both the authorial and editorial side of the gate. Lee and Low’s 2023 diversity in publishing survey shows some progress, with 16.5% of those in publishing identifying as disabled, but this is still an underrepresentation given the 26% of the US population we comprise. And perhaps more importantly, disability is a big tent, with a diversity of intersectional experiences and perspectives.

So even if 16.5% of critics are disabled, the majority of them don’t know sign language or the experience of being deaf any better than a nondisabled person does, and of course, the same holds true for me regarding other disabilities. While a disabled critic would at least aware that ableism exists, and better equipped to extrapolate the potential impacts of one another’s disability within a deeply ableist society, there are still gaps in our cultural competencies and foundations of historical knowledge.

Just like books and their authors, I don’t think a critic’s identity needs to align with the object of their criticism to be worthwhile—that’s a limited view of what both fiction and criticism can do. But I do think failing to consider that we deaf folks might ever have anything to say about portrayals ourselves in art and literature, even as we continue to prove that our art and literature has something to say, is an oversight. Who knows, we may even be able to add something to the discourse not even seasoned critics can.

Take for example…

…James McBride’s The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store. Wildly popular. Gushing review from the Times. The National Book Award Winner, not to mention a prize from Old Man Kirkus. The novel, which takes a magnifying glass to a multiracial community in Pottstown, PA in the 1930s, also features multiple disabled characters, itself a rarity in literary fiction. The characters are at turns, talented, stubborn, entrepreneurial, villainous, and charming, which is to say, many of them are actually three-dimensional humans. As a reader, I found the inclusion of disabled people incidentally in a community exciting, and I enjoyed large swaths of this book. Its narrative construction and characters were often engrossing.

And then there’s “Dodo”. A Black deaf 12-year-old, Dodo (his unfortunate, but probably era-accurate nickname) has lost his hearing in an accident a few years prior to the start of the story. Sometimes, the portrayal of Dodo’s deafness is authentic in the way he notices vibration, how his brain still enjoys music though he no longer hears it the way he used to. But he is also a magical lipreader, conversing in dark forests and basements even though he’s received no training or schooling since his injury.

More disconcertingly, a large portion of the novel’s plot is set in motion when the state attempts to institutionalize Dodo at the nearby Pennhurst Asylum. The dangers and tensions that arise when the neighborhood tries to stop this are compelling. The question that is never answered is why?

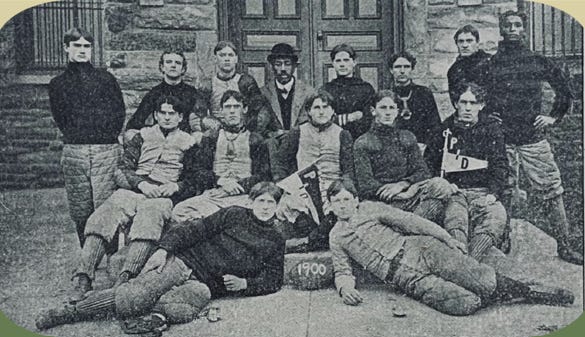

Perhaps because neither writer, nor editor, nor any reviewers were aware or cared to learn that the state-run, residential Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf was operating in Philadelphia, having been an integrated school at least since the Civil War, and likely earlier. More than thirty years prior to the novel’s timeline, in 1895, the real-life Thomas Flowers graduated from PID and went on to become the first deaf person to attend Howard University.

Should it matter, in fiction, if liberties are taken? Not if they’re actually liberties. But in a book that recreates the scenery of Pottstown and surrounding counties with painstaking realism, and includes the real-life musician Chick Webb, the lack of care taken with Dodo’s trajectory stands out. Ultimately, his function is more plot vehicle than person.

In the rare moments we’re given access to Dodo’s thoughts, its mainly for the purpose of giving us a prurient look inside Pennhurst, where we meet a cast of feces-throwing, pedophilic, mentally unwell men, as well as another teenage boy whom Dodo befriends, even as he bestows upon him his own unfortunate nickname, “Monkeypants,” and spends the better part of a chapter perseverating on the way in which his limbs are “tangled up like pretzels” from spastic cerebral palsy.

I doubt these things will matter to most readers—in fact, it’s safe to say given the book’s reception, they haven’t. And because McBride is talented, sometimes they didn’t even matter to me, in that I continued to enjoy much about these characters, their surprising symbioses, and the intricate Philly burbs portraiture. But if the point of the novel is to illuminate the unlikely human ties that bind, characters must be fully human to be part of the tapestry. And this, too, is another kind of realism—as is so often the case when it comes to disability inclusion and representation, the results are an uneven weave.

So for the next couple months, I guess this is a book review Substack?

On deck I’ve got Thomas Fuller’s The Boys of Riverside, Eliza Callahan’s The Hearing Test, and Adele Rosenfeld’s Jellyfish Have No Ears. If you’ve got a recommendation, send it to me in the reply to this email!

Book Biz

25 August (virtual)—Blue Stoop fundraising Master Class, “Disability as Craft” (registration required)

10 October (live in Seattle!)—Deaf Lit Fest, in conversation with Ross Showalter

Hat Biz

Thanks to all who had a bit of fun with me and ordered a hat. We raised a couple hundred bucks for Off the Grid, too—not too shabby! If you missed the hat run or are interested in future tru biz merch, see the below: